- Home

- David C. Noonan

The Man from Misery Page 3

The Man from Misery Read online

Page 3

“She’ll learn her manners,” Garza said crossing his arms, “even if it has to be the hard way.” He turned to Faith. “How do you like the dog now?”

Faith ignored him again, smoothed her damaged dress, rubbed her leg.

Salazar beckoned to the attendant. “Armando, bring Miss Wheeler to Juanita and get her settled. Miss Wheeler, I hope you adjust well to your new life here.”

The attendant approached Faith and motioned her inside. She rose, glared first at Garza and then Salazar. “Murderers,” she whispered, and then she turned and entered the darkness of the main house.

CHAPTER 5 MOONLIGHT ENCOUNTER

Emmet figured he had three more hours of riding before the moon rose out of the bluffs. This stretch of earth was known for hiding hostiles. Tonight’s was a rustler’s moon, full, with no clouds to cloak the light, and Emmet never traveled when a rustler’s moon hung over dangerous terrain—too easy to become a target when all the landscape is backlit and still, and you’re the only thing that’s backlit and moving. He wanted no chance of getting bushwhacked by Comanches or desperados hiding in the bluffs. He estimated a daybreak start would put him in front of the headquarters of the Sabo Canyon Cattle Company by mid-morning.

Emmet mulled over the telegram. Meet me in Santa Sabino. Need help. Bring Betty. Ammo. Friends. Soapy on way. Big pay. Major K. He had brought Big Betty and the ammo, and if he successfully recruited the Thompson twins at Sabo Canyon, there’d be a couple more firebrands added to the shooting party.

Emmet was pleased that the King had reached out to Soapy Waters, who had also served in Major Kingston’s regiment. Round-faced and ruddy, Soapy was burly as a bear, bald as a cannon ball, and friendly as hell, and he knew munitions better than any man alive. He could gab for hours about any aspect of military weapons: why the four-foot breech-loading Sharps was the choice of long-range marksman like Emmet, why the “Napoleon” was the cannon of choice in bad weather, or why canister shot was superior to grapeshot in any kind of weather.

The moon became a ghost riding the sky behind the mountains, and it climbed high enough into the stars to make further travel risky. Emmet spied a rocky outcrop with some scrub that provided enough cover to put down for the night. No fire—too risky. No clouds meant the desert cold would soon grab the night in its chilly fingers, so he wrapped a blanket around himself and broke out some hardtack for a late supper. After he ate, he leaned in against his saddle, pulled his blanket up, tipped his hat over his face, and nodded off.

Emmet slept a few hours before he was jolted awake by the sound of wagon wheels flailing the ground and war whoops ringing the air. He rolled on his belly. In the moonlit landscape, he saw two men in a covered wagon trying to outrun an Indian attack party.

Of all the chicken-brained stunts, Emmet thought. When he counted five hostiles in pursuit, his instincts flared, and he reached for his long gun. Nestling his Sharps against a rock, he took a bead, pulled the trigger, and took down the closest Indian, who was at the back of the pack from his angle. He reloaded and fired again, making a second warrior pinwheel his arms before hitting the ground. As the wagon whizzed away from him, bouncing and bucking on uneven ground, he figured he had time for one more shot before they’d be out of range. He aimed, breathed in and out, and squeezed off another round, dispatching a third hostile to hell.

Now they were too far away, but Emmet wasn’t finished. He knew he could ride as well as any man on horseback and shoot almost as straight from an attacking gallop. He saddled Ruby Red, unsheathed his repeater, and lit out towards the wagon.

He passed the body of the first downed Indian and recognized the markings as Comanche. They were able riders, and Emmet realized it would be hard to gain enough ground to have decent shots at the remaining two. As he raced towards the wagon, he heard a crack and watched another Indian go earthbound. Emmet figured the man sitting shotgun had finally gotten around to doing his job. When the last Comanche realized his medicine had gone bad, he pulled off to the east and rode back towards the bluffs, disappearing into the scrub wood and shadows.

The wagon slowed, and then creaked to a stop, just as Emmet caught up to it. Two Mexican men sat up front. “Señor,” the driver said, “my brother and I say muchas gracias. We are grateful that you shoot so well.”

The driver was filthy and grizzled with animated eyes. His brother was just as ragged, with jagged teeth sticking out of black-licorice gums. The horses’ panting eased, and Emmet heard muffled sobbing coming from inside the wagon.

“Who’s back there?” he asked.

The shotgun man smiled, and his gold-capped tooth flashed in the moonlight. He pushed the canvas flap back with the barrel of his carbine. Two teenage girls were huddled together, whimpering like frightened animals. Emmet could tell from their ragged clothing they were the children of peasants, likely poor and uneducated.

“You girls okay?” Emmet asked. Neither answered, and they hugged each other more tightly.

“They don’t speak English,” the driver said. “They don’t understand you.”

“Who are they, and where are you taking them?”

Emmet noticed the driver’s brother had swiveled the Springfield around and was lap-leaning it so that the business end was now pointing at him. No time for discussion. In one motion Emmet snatched the barrel with his left hand and pushed it down while jamming his repeater against the man’s throat with his right.

“You saw what I did from a distance,” Emmet said. “You better watch how you hold that gun, or you’ll see how much damage I can do up close.”

“Easy, amigo,” the driver said. “We’re running from trouble, not looking for it.” He turned to his brother and said: “Do what he says, Paco. This man won’t hurt us.”

Paco cradled the weapon in his arms, pointing the muzzle towards the sky.

“My name is Diego,” the driver said. “We’re bringing these girls to Sierra Cabrera. It’s a tiny village just south of Santa Sabino. Father Ramirez, our priest, has a school for orphaned children up there. We’re bringing these girls to him.”

“You took one hell of a chance hauling innocents over unsafe ground like this during the night,” Emmet told him. “In fact, it was flat-out reckless.”

Diego nodded. “We thought we could make good time by switching off drivers during the night and be up in Sierra Cabrera by mid-morning. We never planned on those Indians, though.” He grinned. “You gave these señoritas and my brother and me a nuevo dia . . . a new day.”

At this point, Emmet’s mind bustled with thoughts as to what was going on. Diego told his story with a good dose of conviction, and Emmet didn’t detect any signs that he was flimflamming, but it did strike him odd that there weren’t any trunks inside the wagon, almost as if the only items these girls had in this life were the clothes on their backs. As Emmet chewed on the situation, the driver asked where he was headed.

“That’s not a question that needs an answer right now,” Emmet replied.

“If you ever get up to Sierra Cabrera, you should make it a point to come to see the school,” Diego said. “Father is a most gracious man, and I’m sure he would like to thank you in person for saving his precious cargo from these savages.” As he spoke, he swept his hand behind him in the general direction of the four downed warriors.

Emmet perceived Diego to be a slick talker, his manner a curious mix of grease and grace. He would have loved to chaperone the two brothers back to the orphanage and confirm what they were telling him. But Major Kingston’s plight remained paramount, and that meant picking up the twins in Sabo Canyon and hightailing it to Santa Sabino.

“I’ll try to get up to that school some day,” Emmet answered.

“What’s your name, so I can tell Father when I see him?”

“My name is nobody’s bother,” Emmet said. “You can tell him what I look like. Even better, you can tell him what my long range looks like.” He pulled Big Betty out of her sling and held her up. Her long metal barrel

glinted in the moon glow.

The brothers looked at each other before turning back to Emmet.

“As you wish, señor. Let us say once more, muchas gracias.” Diego flipped the reins, and the wagon wheeled south toward the foothills.

The night’s events left Emmet too riled to sleep, so he decided to move out. The odds of a second war party lurking in the same area were slim. He was further encouraged by the fact that dawn was due in an hour’s time, given the morning star’s hover on the eastern horizon. He pointed Ruby Red towards Sabo Canyon and eased her on. But as he glanced back one last time, the wagon now just a brown shadow blurring into the brightening landscape, he wondered whether he would ever meet up with those ragged men or those frightened girls again.

CHAPTER 6 SANTA SABINO

It hadn’t taken long for Emmet to convince the Thompson twins to join him. Times were hard, and the craving for a dollar cuts deep and makes people more willing to take big risks, especially for big rewards.

Emmet first met the twins when he hired them into his buffalo-hunting outfit. Their father abandoned them at an early age, and their mother raised them by herself. She was a churchgoer and gave her red-headed sons good Bible names: Absalom and Zachariah. But everybody called them Abe and Zack, which, to Emmet’s mind, scumbled the Good-Book gloss off her intent.

Life on the prairie had made them able killers—perfect, Emmet figured, for this mission. Red hair is a prize in any Indian’s scalp belt, so the twins learned as many tricks as possible to prevent their hair from parting company with their skulls. Abe was a wizard with a blade. He could whirl Arkansas toothpicks and Bowie knives with equal flash and flair. Nobody could gut a buffalo, or skin the hide, quicker and cleaner. Zack handled a Sharps rifle well and improved under Emmet’s tutoring, learning how to work the arc of the earth into his aim.

Emmet knew giving the twins the opportunity to make some good money using those skills would be an easy sell. They took leave of the Sabo Canyon Cattle Company that morning and had made good time in the saddle. They were now on the main road into Santa Sabino from the north, which required crossing the Santa Sabino bridge, a large wooden span that arched the San Rafael River.

Emmet saw the bridge in the distance. “Almost there, boys,” he said.

“I can’t believe I’m riding with you again, Mr. Honeycut,” Zack said. “Just like old times.”

Emmet smiled. Abe grunted.

The trio reached the bridge in the early afternoon, crossed, and trotted uphill along the main road into town. Franciscan friars founded Santa Sabino after Spanish soldiers gave up looking for gold and went home. San Lazaro, the original adobe church, remained the centerpiece of the main square. The San Rafael River was good sized—fifty feet across at its widest, five feet down at its deepest—and offered numerous watering points for large cattle herds. And even though the town was a quarter the size of Juarez, its main street was an explosion of bustle, dust, and dung.

“Boys, welcome to Santa Sabino,” Emmet said.

They sat their horses and soaked up the view. Open-air vendors jammed both sides of the main road yammering and haggling—and pushing their wares. Wicker baskets stuffed with chickens sat next to vegetables splayed out in rows on the ground. Carts churned up rust-colored dirt, and smoke from cook fires drifted in gray clouds from whitewashed adobe buildings. The smell of roasting meat scented the air. Colorful flowers burst from pots perched on sills and railings. Donkeys with panniers strained against their loads. Drunks curled up in alleyways, while children squealed and laughed and chased animals through tiny yards. Three scruffy waifs ran up begging for money, so Abe shucked them a few coins.

Emmet liked what he saw and felt. Santa Sabino was centuries old with a rich history, unlike Dixville, which sprang up from nothing ten years ago and was still trying to find its identity, or to create one in the middle of the mesquite and sagebrush. Santa Sabino’s buildings were solid, established, well-constructed, not thrown together like most of the wooden structures and canvas tents in Dixville. Most important, nobody here knew who he was, so he could ride along the streets without affront or insult.

“Mr. Honeycut, your friend is somewhere in this beehive,” Zack said. “How we gonna find him?”

“My guess is that he’ll find us.”

A wagon went by, its wheels grinding and screeching. Once it passed, Emmet could hear a guitar being strummed from inside a cantina to his right. A small slate sign with Carmen’s painted on it hung from a large nail. He decided it was as good a place as any to throw down, so they dismounted, tied up, and walked towards the music.

The inside of the cantina was dark, and it took a few moments for Emmet’s eyes to adjust. An old man with a trim salt and pepper moustache was playing the guitar against the back wall, the creases in his forehead as thin and distinct as the strings he was plucking. A dozen men and women clustered around small wooden tables, and a half-dozen more leaned on a long pine plank that served as a bar. Strings of red chili peppers hung from the ceiling, and baskets of fresh bread were lined up on a small table next to the kitchen. The inviting smells of beans and onions frying on a stove set Emmet’s mouth to watering. He and the twins commandeered the last empty table, and an animated young woman hurried over as soon as they sat down.

“What can I get you?” she asked, widening her eyes.

“What exactly are you offering?” Zack asked with a wink.

Emmet shook his head, chuckled, and said, “I’m sorry, ma’am, but Zack here has always loved a pretty ankle, and everything else that comes attached to it. Pay him no mind. We’ll have a bottle of pulque and three glasses, and as many tacos and enchiladas as you can muster to fill three hungry men.”

As the woman disappeared into the kitchen, Emmet turned to Zack. “You’ll always be part hound dog, won’t you?”

Zack spanked his knee. “Come on, Mr. Honeycut. Tell me she ain’t as pretty as a painted wagon.”

Abe leaned in. “Forget that. What can you tell us about this Major Kingston? What does he look like?”

“He’s a couple of inches shorter than me, but wider. Black hair. Strong jaw. He’s got the eyes of a hawk and the memory of an elephant. He’s confident, but he ain’t arrogant. He’s quiet, but he ain’t soft.”

“How did he make all his money?” Abe asked.

“Family business. Dry goods—wholesale, then retail. The Kingstons were one of the few Tennessee families that the war didn’t bankrupt. The King told me his daddy started salting wagon loads of money away six months before Fort Sumter.”

“So Major Kingston’s a businessman,” Abe said.

“Don’t mistake yourself. Just because he knows commerce don’t mean he ain’t got plenty of sand in his craw. He’s the best darned soldier I ever seen. He wields a saber easier than most men do a soupspoon. I rode with him in the war, although it’d be more exact to say I rode behind him.”

“Sounds like you have a lot of respect for him,” Zack said.

“Yep. He’d work out all the details of our battle plans and leave nothing to chance. We soldiers grasped what we was supposed to do, and when, and where. You boys can rest easy knowing that whatever’s going on up here, the King’s nailed down every last detail to win whatever battle we’re gonna be fighting.”

“I wonder how much money we’re going to get paid,” Zack said, rubbing his hands together.

“Depends on how much fighting we have to do,” Emmet advised him.

To Emmet, the twins were two needles off the same cactus, impossible to tell apart save for a couple of scars that were hidden, by clothing in Zack’s case, or hair, in Abe’s. The big difference was in their personalities. Zack was the talker. He could spin a good yarn around the campfire and hold his own with the rowdiest cowboy storytellers. Some of his best stories were about how folks would mistake him for his brother, or the other way around, and how that would lead to a whole lot of misunderstanding and mayhem. One of his skills was honey-talking young ladies in

to haystacks for some necking. Abe’s was a different tale: he kept to himself and always seemed to be spoiling for a fight.

The woman brought the bottle and glasses over. After he poured three shots, Emmet raised his glass: “To our dead rebel brothers.” He threw back the pulque in one burst and gave a loud hoot. The snake water burned and made him clench his teeth like he had a horse’s bit in his mouth.

“That is some awful gullet-wash,” he said, screwing up his face.

Zack stood and said, “I’ll be right back. I’m out of tobacco. You boys need anything from next door?”

“The señorita will be here with the food any time now,” Emmet said. “You don’t want to miss her, do you?”

“I’ll want to smoke after we eat. I’ll just be gone a couple of minutes. Tell her to keep it hot for me,” he said, bugging out his eyes and licking his lips.

Emmet poured another shot for Abe and himself, but this time he sipped it, twisting the glass back and forth in his hand. As he examined its murky color, two white men rose from a corner table, their meals finished. The larger one wore a denim jacket with a bright red patch on the elbow. The shorter one had long, blond hair that spilled out from beneath his straw hat. They passed Emmet’s table just as the server dropped off the food.

“Thanks, Carmen,” the man in denim said to her, glancing at Emmet and Abe as he spoke.

She responded with another enthusiastic smile.

The man took two more steps towards the door, stopped short, then turned around.

“Wait a minute,” he said pointing at Abe. “I know you.”

Abe pulled his head up from his food, studied the man’s face, bit into a taco, and said, “Never saw you before in my life.”

“No, boy. I know you. Your name’s Zack Thompson.”

“Believe me, sir, we’ve never met.”

Emmet knew that Abe was anything but a genteel man, and calling anyone “sir” was completely out of character for him. He realized what Abe was doing and, more importantly, where the conversation was headed.

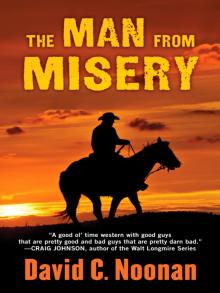

The Man from Misery

The Man from Misery