- Home

- David C. Noonan

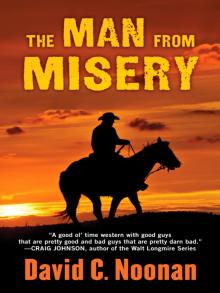

The Man from Misery Page 6

The Man from Misery Read online

Page 6

Kingston tapped the pipe stem against his teeth. “I read there were five victims in all.”

“Turns out her momma and uncle and two other guests were already dead, and the girl was about to join them. Nothing could be done. So people stood there helpless as lame beggars and waited for her to burn. Some folks blocked their eyes. Some prayed. Some covered their ears. When I seen her hair catch fire, I couldn’t watch no more, so I picked up my rifle and done what I done.”

Kingston shifted in his chair, drew hard on the pipe several times. “You know there’s a lot of people who still think what you did was wrong.”

Emmet steeled himself when he heard the change in Kingston’s tone. “I ended that innocent’s torment as quick as that bullet could fly,” he said in a fevered voice, “and I don’t care what you or anybody else thinks.”

“Can killing a child ever be right?”

“No living creature should have to endure that kind of suffering,” Emmet said. “No living creature. Her name was Amy Baxter. She was twelve years old.”

Kingston hoisted both hands in front of him, palms up: “Well, the jury agreed with you.”

“Major, sooner or later, we’ll all have to sit down with a plateful of consequences. I know most people in town didn’t cotton to what I did, and some folks were aiming to make me a guest of the state because they claimed that somebody was fetching a ladder to save the girl, and if I had only waited, she’d be alive, but it was a lie. Once the newspapers learned I was born in Mount Misery, Tennessee, they had themselves a feast and gave me a new nickname.”

“The Man from Misery,” Kingston said in a voice as heavy as stone.

“Leave it to the newspapers to get only half my birthplace right,” Emmet said with a shrug and a cropped laugh.

“Catchy names sell more newspapers.”

“I suppose. Anyway, I was living in a cabin just outside of town when your telegram reached me. Your timing couldn’t have been better. Let me be honest, Major. I can sure use the money you’re offering.”

“I sent for you because I may need your sharpshooter’s eye,” Kingston said, “and I’m willing to pay well for it. Pay very well.”

“I’ve always been good at killing,” Emmet said. He lowered the glass into his lap.

Kingston sucked several quick puffs on the pipe before he set it down and said, “Don’t cumber me with your self pity. Let me be honest. A bullet in the head seems to be your solution to a lot of problems. That wasn’t the first time you mercy-killed somebody.”

Emmet’s body went stiff as oak. He glared at the King and said, “Perryville?”

“Yes,” Kingston said with a quick nod. “Micah True.”

Emmet leaned over and jabbed his finger into Kingston’s chest. “I never agreed with General Bragg’s decision to leave nine hundred wounded men behind while we withdrew to Harrodsburg.”

“And I never agreed with you killing that soldier. Dominican sisters from a nearby convent were already tending the wounded.”

“How could two dozen women take care of nine hundred men? Micah True was a boyhood friend. You saw how that cannon shot sliced him open. He was gut-holed and dying the most painful death there is, and he knew it, too.”

“Emmet, you heard me ask Doc Clayton for opium to ease Micah’s pain, but he said no. Drug supplies were low and had to be rationed among those with a chance of living.”

“So where’d that leave us? Huh? The doc also said Micah had maybe another hour of agony left before he died. My friend’s fists were stuffed with dirt and leaves from where he’d scratched up the ground in his torment. I heard the moans coming out of his mouth with every breath, and if I tried touching him, he’d scream.”

Kingston turned his head towards the river.

“Micah was one of my best shooters, Major. He begged me to help him die easy. ‘Please don’t let the pigs eat me,’ he said. He knew once we retreated, the farmers would let the hogs loose to root through the dead and the wounded. He was afraid the animals were coming for him, and he’d still be alive when they did. You knew that, didn’t you?”

Kingston turned and looked at Emmet. “I knew, but I still couldn’t bring myself to kill him.”

“Not everybody has the stomach for it. That’s what separates you and me. That’s why I suggested you check back in with the big brass while I took care of business. You knew I meant to give him the simple gift of a quick death.”

“That doesn’t mean you were right.”

“I got no regrets, Major. I’d do it for a dumb animal. Seemed cruel to withhold it from one of our own. How many of our men do you think were killed by friendly fire during the course of the war?”

“I have no idea. I hate to think about it.”

“Well, consider it this way. Micah True was just one more Johnny Reb killed by friendly fire.”

Kingston took a moment to glance up at the sky then looked back at Emmet. “Maybe if I had stopped you at Perryville, you’d have thought twice about shooting Amy Baxter. Do you regret killing her?”

Once again, Emmet drained the remainder of his whiskey in one gulp but this time slammed the glass on the table. “No.”

“An honest answer,” Kingston said as he gently set his glass down.

“Well, you know me. I almost always tell the truth.”

“Here again, I can’t say I agree with you, but I’m not going to judge you either.”

“Judge me, Major, or judge me not. I don’t care. Just as long as you pay me for services rendered.”

Kingston jumped to his feet. “Well, that’s probably enough reminiscing for one night.”

“You didn’t finish your whiskey.”

“I’ve had enough,” Kingston said in a waspish tone. “Tomorrow, I’m going to show you and the twins Salazar’s compound. I’m meeting with Salazar the day after tomorrow at his hacienda. That’s the business I was on today. I hope to pay a ransom for Faith and leave here without bloodshed. If I succeed, I’ll give you and the others a handsome reward for showing up. But if I fail, then we’ll take her by force. I’ve brought enough money to either ransom her or pay you and the others. Good night, Emmet.”

“Good night, Major.” He watched Kingston tramp towards the house with heavy steps, the gait of a war-weary soldier. Emmet wasn’t ready to turn in, so he repaired to the porch and rolled a smoke. As he puffed in the shadowed quiet, his cheeks flushed, his mind awhirl from the liquor, his thoughts turned darksome as he brooded on his past: the war, the hotel fire, the trial, and the woman he never got to marry.

CHAPTER 10 THE DINING ROOM

Faith and Valencia huddled on their cots at the far end of the storage room while the other girls conversed in hushed voices.

“I wonder why they’re letting us eat in the main dining room tonight?” Valencia asked.

“Don’t know,” Faith said. “Don’t care.”

Valencia brushed several strands of jet-black hair out of her face and said, “I hope the food will be good.”

“How can you even think about food?” Faith asked.

Valencia blushed, bit her lip. “There’s nothing we can do, so we should do what they say.”

“Maybe for now,” Faith said, “but there’s always something we can do. I just need to think of what it is.”

“How old are you, Faith?”

“Sixteen.”

“Same as me,” Valencia said, a pulse of energy lifting her voice. “My father was working in the Dolores silver mine when Garza and his men came. They paid my mother twenty pesos for me.”

“She didn’t put up a fight?” Faith asked, the black memory of her own abduction seared into her consciousness.

“What could she do? I have five younger brothers and sisters. She had to worry about them, too. I think they would have killed her if she didn’t accept the money. Twenty pesos was better than nothing.”

“Twenty pesos? That buys five chickens,” Faith said. “Is that all you’re worth to your family?”

Valencia dropped her head, and tears rolled down her cheeks.

“I’m sorry,” Faith said. “That was unkind. I know you had no control over what happened.” Faith kneaded Valencia’s shoulder with her right hand.

The dark-haired girl sniffled, wiped her eyes, and offered a faint smile. “Do you have brothers and sisters?”

“I’m an only child. My parents served the South during the war and tended the wounded. My father helped with the soldiers’ prayers. My mother was a nurse.”

“Do you remember the war?”

“I was too young. When the war ended, we moved to Texas so my parents could continue helping other people. That decision caused a lot of problems with my grandfather. He was rich, and he resented my mother walking away from her inheritance.”

“Why did she do it?”

“She was more interested in healing. I learned a lot about nursing from her. She delivered babies, stitched wounds, made medicines. Folks would come from far away to see her and listen to my father. He preached to them that God loves us all.”

“Do you think God loves Garza?”

A chill shot up Faith’s spine, and she gritted her teeth. “I don’t know,” she said, choking on the words. Just the sound of the killer’s name stirred the bile in her stomach.

“Did your parents take the money?”

Faith’s temples started to ache. Warring thoughts and emotions jostled inside her brain, some of them unholy, contemptible. She opened her mouth, but no words came out. She glanced at the ceiling, trying not to think about the horror she had experienced, but she couldn’t put it out of her mind. She shuddered and fought back sobs.

Now Valencia’s comforting hand rubbed Faith’s shoulder. Faith opened her mouth again, and, this time, words came out. “They refused to take the blood money, and Garza killed them. Your mother was right to take it. At least she’s still alive.”

“So you’re an orphan now,” Valencia said, still massaging her shoulder.

Once again, Faith was unable to speak. She nodded as tears dripped off her cheeks.

A heavy rap on the door startled the girls. From the other side, a voice yelled, “Dinner.” The door swung open. A guard entered and pointed the girls towards the hallway.

Faith dried her eyes with the backs of her hands and followed the eight other girls into a large dining room. She marveled at the extravagance. A marble fireplace dominated one wall of the room. On the opposite wall, a ten-foot-wide hutch carved from Mexican pine displayed multiple place settings, pitchers, serving dishes, and glasses. Two wrought iron chandeliers hung from the ceiling, each with six red pillar candles. Three lit candelabras on the table accentuated the yellow tablecloth. Salazar and Garza occupied chairs at either end of the table. The girls took their seats in the hand-carved chairs, and two older women served them steaming bowls of soup.

“Juanita will be observing your table manners,” Salazar said, “and teaching you proper etiquette as you eat. Your new homes will be quite grand compared to what you’re used to, and you don’t want to embarrass yourselves. We had you skip lunch today so you’d be extra hungry for this comida. Now, ladies, you may begin.”

“Shouldn’t we say grace?” Faith asked.

“No,” Salazar snapped, tapping his chest and then pointing to Garza. “We are the creators of this feast.”

The girls picked up spoons and attacked their bowls. Faith savored the blend of chicken broth, onions, garlic, and celery. She saw one of the girls pick up the bowl with both hands and slurp its contents. At once, Salazar cued Juanita, who approached the girl and lowered her arms with one hand and passed her the spoon with the other. As the girl glanced at the smirking faces around the table, Juanita said, “It’s okay, dear, you’re here to learn.”

Garza reached over and picked up a guitar resting against the wall. He smiled and said, “Let me play something to enhance your meal,” and then he filled the room with the sweet notes of a romantic song.

As Garza played, Salazar said, “Ladies, if you cooperate, you’ll live fine lives indeed. Soon, you’ll be wearing beautiful dresses and expensive jewelry and living like queens.”

After the girls finished the first course, Salazar rang a small bell, and Armando entered through the right door to collect the bowls. Faith recognized him as the boy who had brought her the welcome glass of lemonade when she first arrived. The two women reappeared at the left door with skillets of food. A third woman entered, opened the hutch, and removed a stack of plates. The girls received heaping portions of beef, beans, tortillas, and salsa, and they shared pitchers of juice squeezed from bananas and mangoes.

“These will be exciting days for you,” Garza said as he plucked at the strings. “New romance is always exciting.”

Faith sneered at him. Garza finished the song and transitioned to a slower ballad. His fingers rolled up and down the instrument as he hummed in a relaxed tone. Faith could tell that several girls were enchanted by the music but noticed Marisol peering down at her plate and stifling a sob.

“Yago, perhaps something more upbeat, yes?” Salazar said as he pumped his head twice at the doleful girl.

Garza nodded and truncated the song with a flourish of strums before launching into a more spirited tune. In perfect tempo, he moved down and across the strings with his index finger, and then slapped the upper bout of the guitar. The effect enlivened the notes and, at the same time, showcased his musical prowess.

Showoff, Faith thought.

Juanita circled the table, offering assistance and pointing out mistakes. “Head up, Jacinda,” she said to one girl whose face hung inches from her plate. “Chew with your mouth closed,” she told another as she squeezed her own lips together with her thumb and forefinger. “Here’s the proper way to cut meat with a knife,” she said to a third and demonstrated with the girl’s utensils.

Juanita lifted a tiny wooden cross hanging from Toya’s neck with one finger and asked, “Señor Salazar?”

Salazar nodded. “I must have missed that when I was with the tailor.”

Juanita removed the cross from the girl’s neck.

“But my parents gave it to me,” Toya protested.

“We’ll replace that with a much more expensive necklace, señorita,” Salazar assured her. “Soon you’ll be wearing gold instead of wood. Right now, we’re going to take a short rest before we enjoy dessert. Juanita, while we digest our food, tell us what you’ve learned from your talks with our new guests.”

Juanita removed a folded piece of paper from her apron pocket and recited each girl’s abilities. Six cooked. Six sewed. Three were literate. Valencia could bend her fingers back until they touched the top of her hand. Belinda knew how to juggle. Faith spoke English and Spanish and also had excellent nursing skills. None of the nine girls admitted to ever having sex.

“Miss Wheeler,” Salazar said. Faith turned to him and noticed his eyes strolling up and down her. “You put these girls to shame, my little mustang. You speak two languages. You read. You cook. You sew. You know how to take care of sick people. You are truly remarkable. Now if we can just drive that Bible babble out of you.”

Garza chuckled. “Watch out, Enrique. Bible thumpers have queer religious notions, and they rarely smile.”

Faith wasn’t listening. Her mind was set on filching the steak knife on her plate.

Garza leaned the guitar against the wall. Faith watched his eyes float from girl to girl before they settled on Belinda. He clapped his hands together and said, “So you know how to juggle.” He walked over to a straw basket in a corner of the room, pulled out three balls of colored yarn, and tossed them to the girl. “Please, show us.”

“I need to be standing,” Belinda said with a pained look.

“Of course,” Garza said. He extended his palm and invited her to rise by wiggling his fingers.

Faith saw her chance. When she believed all eyes were on Belinda, she snatched the knife and slipped it under her napkin. With two fingers she hiked

the hem of her smock up several inches, leaned forward to slide her chair closer to the table, and tucked the knife beneath her garment. She glanced up at Garza who, like Salazar, was watching Belinda.

She started to exhale a sigh of relief but stopped abruptly—Armando was in the doorway, staring at her. Pangs of panic wracked her, and she went numb as he walked around the table towards her. He leaned in on her right side and asked, “May I take your dish, señorita?” He winked at her so only she could see. Her numbness disappeared, and a warm feeling of calm descended on her when she realized he wasn’t going to expose her.

“Thank you,” she whispered. “That would be fine.”

Belinda juggled for several minutes and ended with some fancy flourishes without dropping a ball. When she stopped, the group clapped at her dexterity. She bowed at the applause, looked at the floor, and said that her brother had taught her.

“Can you juggle four balls?” Garza asked, as he pointed to the basket of yarn.

“Not yet, but my brother says he’s going to teach . . .” She stopped speaking, her small smile disappeared, and she sat down.

Armando removed the remaining dishes and silverware just as the older women brought in dessert—sopapilla, two layers of fried dough with honey drizzled between them. Faith heard several girls gasp with delight at seeing the pastries.

“Wait until everyone is served,” Juanita advised, anticipating their eagerness. They began eating as soon as the last dessert plate touched the table. “Like ladies,” Juanita reminded them. “Like ladies.”

Salazar jammed his thumbs in his belt and poured his voice around the table. “After you finish your desserts, Juanita will discuss with you what to expect in the bedroom. Ask Juanita as many questions as you’d like.” Salazar yanked his thumbs out and stood. “I’m done here. Yago, are you coming?”

Garza leaned back in his chair and grinned. “No, I think I’ll stay. I’m curious as to what kind of questions these girls might have. And who knows? Maybe I can help answer them and put their minds at ease. They might benefit from hearing a man’s point of view on what is expected.”

The Man from Misery

The Man from Misery